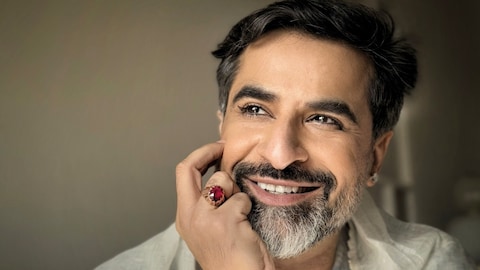

Suvir Saran would like you to clean your glasses

A deliciously unfiltered hour with the man who wrote 'Tell My Mother I Like Boys'—and means every word.

Five minutes into my Zoom call with Suvir Saran, before I can even get to the cookie that opens his memoir, he stops me mid-sentence to say, very seriously, “You have stains on your glasses. Please wipe them.” This is not a metaphor. This is a Michelin-starred chef and author (who has previously published three cookbooks)—and recently wrote the memoir, Tell My Mother I Like Boys—politely but firmly asking me to clean my lenses because clarity matters. I comply. (Let’s call it mutual respect, not obedience).

This sets the tone for the next hour: Intimate, unruly, slightly ‘filthy’, and deeply precise. Saran adjusts his camera, compliments my lighting (“You look gorgeous”), and announces—gleefully—that everything we’re saying is being recorded and will make for excellent trailer bites. At one point, he asks me my “position.” At another, he declares himself the emperor of gay India. Somewhere in between, he talks about shame, hosting, Grindr, grief, and why vanilla is both a culinary and sexual sin.

Growing up, coming out, wanting more

The memoir at the centre of this madness, Tell My Mother I Like Boys (published by Penguin Random House India), is not a coming-out story in the neat, Western sense. It’s a book about hunger—literal and emotional—about growing up in Delhi as a boy who was dressed like a doll, adored until puberty betrayed him, and then quietly abandoned. “I was paraded from age five to 11 as the prettiest girl South Delhi had ever seen,” he tells me. “And then the first hair came out. The girls left. My voice cracked. I failed sixth grade.”

He says it without drama—like recalling a recipe he’s cooked too many times to romanticise. In the book, puberty isn’t a moment so much as an invasion: A hostile takeover where the body turns into contested ground and desire shows up before the words for it do. “That’s when I realised,” he says, “that I was becoming something I also wanted to be with. A lover.”

What Saran has now, abundantly, is language. For sex, for food, for fear, for survival. When I ask him what the most “insignificant” food to shape his life has been, he answers instantly: “Cookies and cream. And doughnuts.” Then, because he’s Suvir, he adds, “Doughnuts! Cream or not.” I fail to regain control.

There’s a reason this book lands the way it does. Saran came out to his parents over three decades ago, and in his telling, that moment burnt shame to the ground. “From that day on, I had nothing to hide,” he says. “Anything you know about me, my parents know.” His father, who thanked him for becoming a role model for other queer kids from the Global South, looms large. His mother is the emotional axis. “If my life were a thali (traditional meal),” he says, “my mother would be the thal (platter). Omnipresent. Without her, nothing works.”

Cities, sex, and the politics of space

We talk about cities like former lovers you still stalk on Instagram. Delhi made him queer—and terrified. “I cried myself to sleep for 10 years,” he says. Mumbai taught him what it meant to be othered for his body—“chikna, gora” (fair, pretty boy)—but also gave him freedom. New York gave him success, fame, and fear in equal measure. “I was beaten once because they thought I was someone’s farmhand.” He pauses. “The world is never safe. It only pretends to be.”

And then, because we are Cosmo, I ask the important question: Which city made him boldest in bed? “India,” he says, without hesitation, naming a country instead. Not New York. Not San Francisco. India— because he can host. Hosting, according to Saran, is not about hospitality; it’s about power. “In India, most people don’t have a place,” he explains. “They have hotels. Shame. Fear. Money. I live alone. I can host. I’m the Raja.” In his worldview, desire is infrastructural. Safety is erotic. Privacy is foreplay. It’s not about excess or exhibitionism—it’s about honesty. About being able to “f**k”, love, and live without pretending you’re someone else.

This is also why he’s on Grindr—with his real face. “I have nothing to hide,” he says. “If someone sees me and thinks, ‘If he can be out, maybe I can too’—that matters.” He claims to hate flattery, insists he’s happiest alone, and blocks people he knows. I don’t believe all of it. I like him anyway. For someone who flirts relentlessly, Saran is surprisingly tender about love. The most romantic thing anyone has ever done for him? “Loved me fully,” he says. “Gave me their time. Their loyalty. Their life.” He pauses. “And I didn’t see it until I lost them.” He quotes softly: “Jo mil jaaye wo mitti hai, jo kho jaye wo sona” (what stays feels familiar like dust; what’s lost becomes precious gold).

If the book asks readers to witness his life, he hopes it also takes something from them. “Their bias,” he says. “Their fear.” Shame, after all, belongs to the world—not to the boy.

By the end of our conversation, he tells me he’s always in love. Not always with a person—sometimes with music, sometimes with cooking, sometimes with tomorrow. “I love today,” he says. “Because I can still do something with it.” Before we hang up, he asks me if I got what I wanted. I tell him I did—and then some more. He offers to keep going, to make it “more saucy, more Cosmo.” I check my glasses. Clean. Crystal clear. Some men want to be desired. Suvir Saran wants to be seen— properly, sharply, without smudges. Preferably with the lights on.

Cosmo Quiz

Kiss: Soft or savage?

Savage

Foreplay: Underrated or overrated?

Underrated

Turn-on: Confidence or kindness

Kindness

Texting after sex: Yes or no?

Depends on how they text

Favourite post-sex snack?

Foreplay

Biggest ick: Ego or dishonesty?

Ego

Bedroom vibe: Lights on or lights off?

Lights on

Aftercare: Essential or optional?

Optional

Jealousy: Hot or hell?

Hell

Fantasy: Private or shared?

Both

This article first appeared in Cosmopolitan India's January-February 2026 print edition.

Also read: Why queer love on screen feels powerful for a generation raised in silence

Also read: Five creatives spill the beans on their all-time favourite rendition of love